Understanding React Server Components

React Server Components have lifted server-rendering to be a truly first-class citizen of the React ecosystem. They allow developers to render some components on the server, while attempting to abstract away the divide between the client and server. Devs can interleave Client and Server Components in their code as if all the code was running in one place.

Yet, abstractions always come at a cost. What are those costs? When can you use RSCs? Does reduced bundle size mean reduced bandwidth? When should you use RSCs (React Server Components)? What are the rules that devs have to follow to use them properly and why do those rules exist?

To answer these questions, let's dive together into how React Server Components really work, under-the-hood. We'll do this by examining two sides of the RSC story: React itself and React meta-frameworks. In particular, we'll look at both React and Next.js internals to form an accurate mental model of how the RSC story comes together.

Note

This post is aimed at developers who are familiar with using React. It assumes you know what components and hooks look like.

It's also assumed you're familiar with Promises, async, and await in JavaScript.If not, you can watch my under-the-hood YouTube video on Promises, async, and await.

First, we must establish some fundamentals necessary to understanding how RSCs work.

The DOM and Client Rendering

React co-opted the term "render". When we say the browser "renders" our page we are referring to the actual work of painting the DOM to the screen. The browser takes the DOM (the tree of elements) and the CSSOM (the tree of computed styles), calculates how elements should be laid out, and then paints the appropriate pixels to the screen.

React instead uses that same term to mean "calculating what the DOM should look like". The values our component functions return tell React what the DOM should look like.

Thus, in the world of React (and other frameworks who have since followed in React's footsteps), when we say "client rendering" we're talking about our component functions being executed in the browser.

React's version of "rendering" doesn't always lead to actual browser rendering, since it's possible the DOM already looks the way React thinks it should.

When React says "client rendering" we're talking about our component functions being executed in the browser.

In fact, a major point of React's core architecture (along with all other JS frameworks) is to limit how much its internal code updates the DOM.

Tree Reconciliation

Inside React's source code are calls to browser DOM APIs like appendChild to update the DOM in the client. React chooses when to execute those browser DOM APIs via tree reconciliation and diffing.

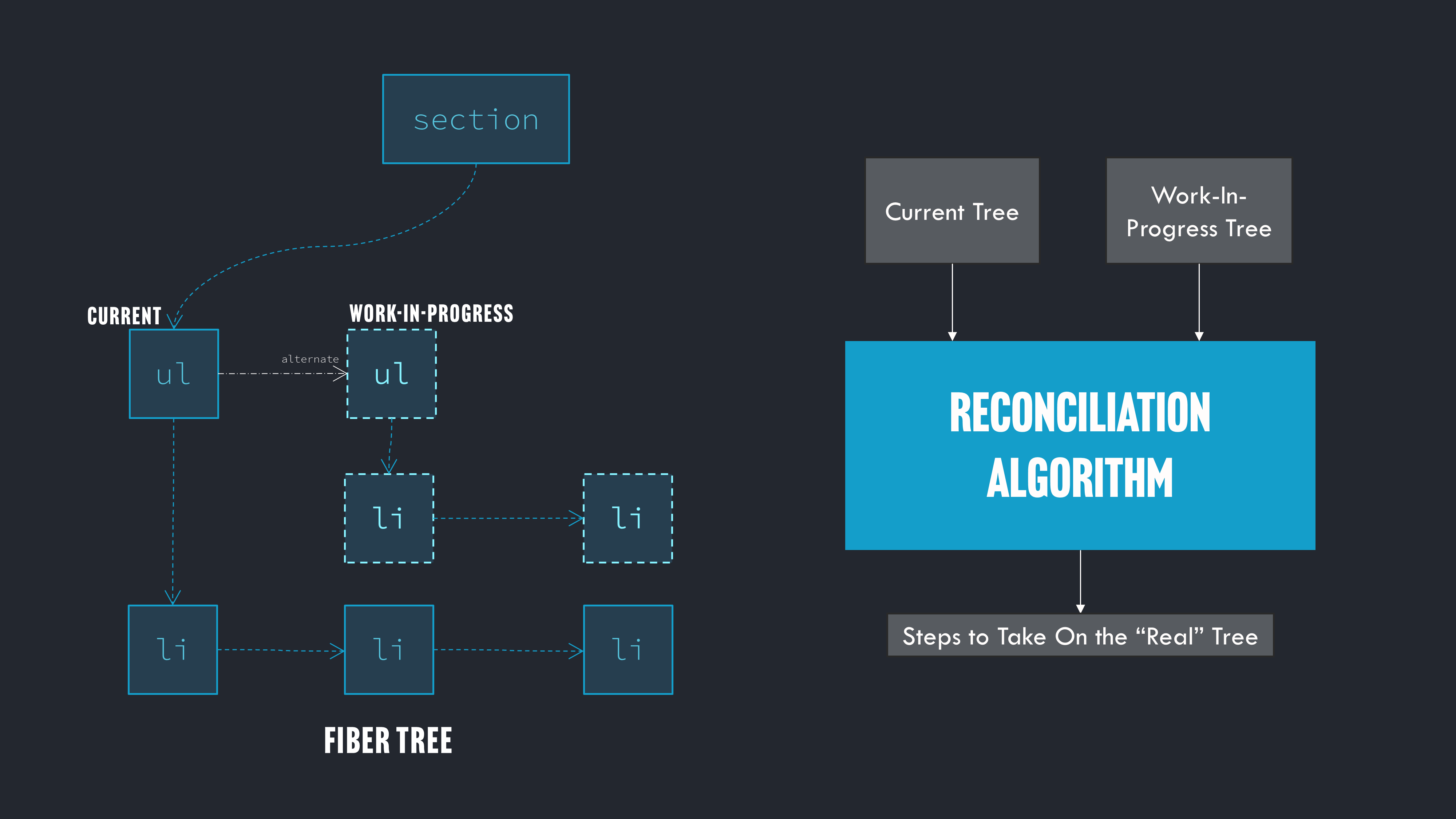

As we talked about in my post on React Compiler, React keeps track of what the DOM both currently looks like and should look like in a tree of JavaScript objects, where each node is called a Fiber.

React calculates what the DOM should look like (called "Work-In-Progress") and compares it to what the DOM currently looks like (called "Current") in two branches of that JavaScript object tree.

It then reconciles the difference between those two trees, calculating the steps needed to convert the current tree into the work-in-progress tree. Those steps are the "diff" or "patch".

Once it finishes that calculation, all against simple JavaScript objects, it knows what steps to take in the real DOM. By finding the minimum number of steps to take, it minimizes how much it has to update the DOM, since updating the DOM is expensive and causes the browser to re-render (layout elements and paint pixels).

Updating the DOM in the client has the advantage of preserving state as you update the UI. For example, a user can type information into a form, React can update the UI based on some event, and the text stays in the form (unlike if the page refreshed).

Thus React is focused on updating the DOM in the client, while trying to be as efficient as it can in doing so, doing work first against a fake DOM. This fake copy of the DOM's structure in JavaScript is generally called the "Virtual DOM".

Is "Virtual DOM" the Right Phrase?

We used to call the collection of JavaScript objects in React that are structured like the DOM the "Virtual DOM". But React doesn't like that term now because you can target other things like native iOS and Android apps (React Native) to render to.

In fact, there are multiple trees that React deals with, a tree of React Elements (JS objects) that your function components return and a Fiber tree (also JS objects) that React Elements are converted into and used to store state among other things.

While I usually refer to these two trees more specifically, for this post I'll use the long-standing colloquial term "Virtual DOM" because it's useful in keeping track of how RSCs work.

Calculating the Virtual DOM is what React refers to as "rendering": executing your function components to determine what the real DOM should look like. This all happens inside the JavaScript engine executing the functions, and until reconciliation doesn't touch the real DOM at all.

As it turns out, understanding that React co-opted the term "render" goes a surprisingly long way in helping explain RSCs accurately.

To understand RSCs we need to have clear in our minds the difference between what we usually mean in web dev by client and server rendering, and React's focus on the generation of the Virtual DOM.

When React says "render", you don't actually necessarily see anything happen...

Let's keep track of these various "render" meanings as we go. We'll call the typical (non-React) definitions "classical" and start building a dictionary entry for our web dev vocabulary:

- rend·er

- /ˈrendər/

- verb

- 1. (Classical Client-Side) To take the DOM and CSSOM, compute layout, and paint pixels to the screen.

- 2. (React Client-Side) To execute function components in order to build and update the Virtual DOM.

The DOM and Server Rendering

Moving forward in the RSC story means moving backwards in time. A core idea of the internet has long been HTML being delivered from a server.

Creating your HTML on the server (perhaps using server technologies like NodeJS or PHP) is classically called "server-side rendering" or "server rendering". This is already different than what we meant by classical client rendering. Historically server rendering has meant "generate strings of HTML" on the server.

This comes with some advantages. Browsers translate HTML into the DOM very quickly. As a result HTML renders in the browser fast. Updating the DOM via JavaScript is slower in comparison. Also, your server is closer to your database or file storage, so those operations are more efficient.

A downside is that, while the client can request the HTML again, you lose state (the page refreshes).

This has been the balancing act for many years in web development: server-rendered HTML appears quickly, but DOM updates via client-side JavaScript let you make changes while maintaining the state of the page.

React doing both is nothing new. While React does DOM updates via client-side JavaScript, developers have long been able to server-render React components (SSR) as well.

Master React From The Inside Out

If you are enjoying this deep dive, you'll love and benefit from understanding all of React at this level. My course Understanding React takes you through 17 hours of React's source code, covering JSX, Fiber, hooks, forms, reconciliation, and more, updated for React 19.

Learn More →The server (running its own JavaScript engine via something like NodeJS) executes the components and generates an HTML string to send to the client, but there's a big caveat: all the JavaScript code for those same components also had to be sent to the client and executed.

Why? So the Virtual DOM could be built from what those function components return. The Virtual DOM is used to "hydrate" the real DOM, meaning for example we know what click event inside what function component to run when a button is clicked. Remember, React needs both trees (DOM and Virtual DOM) to exist in the client to work. So, SSR in React means executing your functions twice (once on the server to make HTML and once on the client to make the Virtual DOM).

Here's a visualization of the SSR/hydration process to help:

Enter React Server Components. RSCs add the ability to intermingle React components that execute on the server with React components that execute on the client without sending and re-executing the server components' JavaScript code. This also comes with the possibility of initially rendering HTML on the server, before beginning to update the DOM in the browser.

How?

First, let's update our dictionary entry:

- rend·er

- /ˈrendər/

- verb

- 1. (Classical Client-Side) To take the DOM and CSSOM, compute layout, and paint pixels to the screen.

- 2. (React Client-Side) To execute function components in order to build and update the Virtual DOM.

- 3. (Classical Server-Side) To generate HTML to be sent to the client to build the DOM.

- 4. (React Server-Side SSR) To execute function components in order to generate HTML to be sent to the client to build the DOM.

What About Server-Side Generation?

One thing we aren't talking about here is SSG (Server-Side Generation). That means pre-generating the HTML while building the app (that is, preparing it for deployment). You can do this for both Client and Server Components.

SSG would have the same definition as SSR in our dictionary entry. Differentiating SSG and SSR doesn't help us much in this post, so I won't talk about it much, but it is supported.

We said React needs both full trees, DOM and Virtual DOM, to be sitting in the browser's memory to work. So how do React Server Components get away with only executing on the server, without needing their JavaScript code to be downloaded and executed by the client?

React needs both full trees, DOM and Virtual DOM, to be sitting in the browser's memory to work.

In other words, how does React build the Virtual DOM in the browser for the part defined by functions executed on the server?

Flight

In order to support executing function components on the server, and then building the Virtual DOM from their results on the client, React added the ability to serialize the React Element tree returned from server-executed functions.

Serialization and deserialization often end up meaning "convert objects in a computer's memory into a string" and "convert strings back into objects in a computer's memory".

In this case, the results of our component functions need to be serialized and sent to the client.

Let's suppose I'm making a simple app where I will track how many students have enrolled in my React course. I'll start with a basic RSC in Next.js. It will be executed on the server.

export default function Home() {

return (

<main>

<h1>understandingreact.com</h1>

</main>

);

}

Isomorphic Components

If a component can be executed on the server or the client it's referred to as "isomorphic". My above function doesn't do anything server-specific (like connect directly to a database or read a file off the server), so it could instead have been executed on the client, and React could build the Virtual DOM from its results directly as normal.

If a function is isomorphic, then it can be shared. Both Server and Client Components can import and use them.

To prevent having to send this function to the client for execution, its results need to be serialized. Inside React's codebase this serialization format is called "flight" and the sum of data sent is called the "RSC Payload".

My simple function's result ends up serialized into this:

"[\"$\",\"main\",null,{\"children\":[\"$\",\"h1\",null,{\"children\":\"understandingreact.com\"},\"$c\"]},\"$c\"]"Let's format it for easier examination (credit for the excellent RSC parser from Alvar Lagerlöf):

{

"type": "main",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": {

"type": "h1",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": "understandingreact.com"

}

}Can you see the structure of the Virtual DOM? Our main and h1 elements are here as well as our plain text node. We can see what is being passed as props, specifically the standard "children" prop intrinsic to React.

We're simplifying here, there's more to the format than this, and a meta-framework may add more to it for their own purposes. For example, identifiers for what kind of thing is being placed in the tree "like 'f:' for 'flight'". But a simplified example is sufficient for our understanding.

While React is providing the serialization format, the meta-framework (in this case Next.js) must do the work of ensuring the payload is created and sent to the client.

Next.js, for example, has a function in its codebase called generateDynamicRSCPayload.

The meta-framework is ensuring that the payload is generated and sent to the client. Thanks to the payload, on the client React can build an accurate Virtual DOM and do its normal reconciliation work.

Meta-Frameworks and Server Rendering

We said earlier that rendering HTML from RSCs was a "possibility". That's because it's optional - it's up to the meta-framework if it does so or not. But it makes sense to do so.

Remember we said perceived performance was an important metric. If you're already executing code on the server, and you can stream back HTML, you should, because the browser will render that HTML quickly, resulting in a faster perceived experience for the user.

If a meta-framework is perceived as slow, no one will use it. So React meta-frameworks implementing RSCs need to do both kinds of server rendering: the classical kind and the React kind.

Classical server rendering (generating HTML) gets you pages that render (painted by the browser) quickly, while React-style server rendering (RSC payload) gets you the Virtual DOM for future stateful updates.

Thus, in practice, an RSC will result in what is called the "double data problem". You will send the same information from the server in two different formats at the same time: HTML and Payload. You're sending the info needed to immediately build the DOM (HTML) and the Virtual DOM (Payload).

Here's a visualization:

For our simple example, Next.js returns HTML, which the browser uses to build the DOM:

<main>

<h1>understandingreact.com</h1>

</main>and the Payload, which React uses to build the Virtual DOM:

{

"type": "main",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": {

"type": "h1",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": "understandingreact.com"

}

}The HTML being sent allows the page to be browser rendered quickly. The user sees something right away. The Payload being sent lets React finish the work of making the page interactive.

Sometimes it's argued that the cost of this repetition of data is negated by compression algorithms (like gzip) which servers use before sending responses. However, HTML and the JSON-ish payload are two different formats, so the repetition is obfuscated enough that the double data still makes an noticeable impact on bandwidth.

Abstractions have a cost. The cost here is sending the same information twice.

With all this in mind, though, we now have a complete list of 5 different definitions for "render"!

- rend·er

- /ˈrendər/

- verb

- 1. (Classical Client-Side) To take the DOM and CSSOM, compute layout, and paint pixels to the screen.

- 2. (React Client-Side) To execute function components in order to build and update the Virtual DOM.

- 3. (Classical Server-Side) To generate HTML to be sent to the client to build the DOM.

- 4. (React Server-Side SSR) To execute function components in order to generate HTML to be sent to the client to build the DOM.

- 5. (React Server-Side RSC) To execute function components in order to generate flight (payload) data to be sent to the client to build and update the Virtual DOM.

Notice similarities across the React definitions? For React rendering always means "executing function components", and Client and Server Components both provide what is needed to build and update the Virtual DOM.

Streams, Suspense, and RSCs

Performance is always a concern when building an application. But there are two kinds of performance: actual performance and perceived performance.

HTTP and browsers have long supported streaming as a way to improve both kinds of performance. Things like NodeJS' Stream API and the browser's Streams API (in particular the browser's ReadableStream object).

React (and any meta-framework that wants to support RSCs) utilize these core technologies to stream both HTML and Payload data. Streaming really means sending small amounts (called chunks) at a time. The client can work with those smaller amounts of data as they come in.

Thus with streams the question isn't "what was sent" but "what has been sent over time".

The browser is designed to handle HTML streaming over the network. It renders (lays out and paints) the page as HTML streams in.

Similarly, React accepts a Promise which later resolves to RSC Payload data. Next.js, for example, sets up a ReadableStream on the client, reads in the stream from the server, and gives it to React as it comes in. React's entire approach to server rendering is centered around streaming content in where needed.

In fact, the Flight format itself includes markers for things that haven't completed yet. Like Promises and lazy loading.

For example, suppose I setup a server component to be async, and await a timer:

// components/Delayed.js

async function delay(ms) {

return new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, ms));

}

export default async function DelayedMessage() {

await delay(5000); // 2 second delay

return (

<p>This message was loaded after a 5 second delay!</p>

);

}

// page.js

import DelayedMessage from "./components/DelayedMessage";

export default function Home() {

return (

<main>

<h1>understandingreact.com</h1>

<DelayedMessage />

</main>

);

}The async function returns a Promise. Thus the resulting Payload will look like this:

{

"type": "main",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": [

{

"type": "h1",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": "understandingreact.com"

}

},

{

"$$type": "reference",

"id": "d",

"identifier": "L",

"type": "Lazy node"

}

]

}

}Notice that the place where the DelayedMessage component should be is instead marked with a special "L" identifier, marking a place where content will appear later.

If you run this code, though you'll find that instead the entire page takes 5 seconds to load, rather than just the delayed message.

That's because React deals with Promises and lazy loading using the special Suspense functionality designed for the client. If we update our component to use Suspense:

import DelayedMessage from "./components/DelayedMessage";

import { Suspense } from "react";

export default function Home() {

return (

<main>

<h1>understandingreact.com</h1>

<Suspense fallback={<p>Loading...</p>}>

<DelayedMessage />

</Suspense>

</main>

);

}and we run the page, it will instead show the fallback first and then show the delayed message after 5 seconds. But notice this component still runs on the server! How can you opt into Suspense on the server? You don't. The Payload returned from the function, when processed on the client, builds a Virtual DOM that includes a

The Payload looks like this:

{

"type": "main",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": [

{

"type": "h1",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": "understandingreact.com"

}

},

{

"type": {

"$$type": "reference",

"id": "d",

"identifier": "",

"type": "Reference"

},

"key": null,

"props": {

"fallback": {

"type": "p",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": "Loading..."

}

},

"children": {

"$$type": "reference",

"id": "e",

"identifier": "L",

"type": "Lazy node"

}

}

}

}

}Notice both the fallback (as a prop) and what is loaded after the Promises resolves (the "Lazy node", in this case the DelayedMessage) are all there.

The Payload both itself streams in in chunks and references spots in the Virtual DOM where Promises will later be resolved. In this way React and RSC-supporting meta-frameworks endeavor to improve both real and perceived performance for the user, letting the user see UI as soon as possible.

But where does flight data stream to really? It must be somewhere in the React codebase.

Giving React the Payload

To support RSCs, React added to its codebase the ability to accept the Flight format (a string) and convert it to React Elements in functions like parseModelString.

It's up to the RSC-supporting meta-framework to execute those React APIs, sending the appropriate data.

For example, Next.js adds some extra wrapping components to your app, where it passes in a stream of Payload data.

It looks like this:

<ServerRoot>

<AppRouter

actionQueue={actionQueue}

globalErrorComponentAndStyles={initialRSCPayload.G}

assetPrefix={initialRSCPayload.p}

/>

</ServerRoot>Next.js adds a component to your component tree, above the AppRouter called ServerRoot. From there it streams to AppRouter the RSC Payload data.

Ultimately that data is streamed to React's Promise-based APIs for accepting the Flight format.

Thus React provides APIs for building its Virtual DOM from the Payload, and Next.js (or any RSC-supporting meta-framework) has its own mechanisms for getting that data to React after components execute on the server.

Out-of-Order Streaming

There's more to the streaming story though. Different components may complete executing at different times. As Payload chunks stream in, how does React know where in the Virtual DOM (and thus the DOM) to place them?

If we look at the DOM again where we use our DelayedMessage component, it looks like this at first:

<main>

<h1>understandingreact.com</h1>

<!--$?-->

<template id="B:0"></template>

<p>Loading...</p>

<!--/$-->

</main>React leaves placeholders like template with a special ID and HTML comments to note where content should be dropped once the Promise Suspense is waiting for resolves.

The fallback is in the DOM, but when the Promise resolves some new JavaScript is streamed to the page:

$RC = function(b, c, e) {

c = document.getElementById(c);

c.parentNode.removeChild(c);

var a = document.getElementById(b);

if (a) {

b = a.previousSibling;

if (e)

b.data = "$!",

a.setAttribute("data-dgst", e);

else {

e = b.parentNode;

a = b.nextSibling;

var f = 0;

do {

if (a && 8 === a.nodeType) {

var d = a.data;

if ("/$" === d)

if (0 === f)

break;

else

f--;

else

"$" !== d && "$?" !== d && "$!" !== d || f++

}

d = a.nextSibling;

e.removeChild(a);

a = d

} while (a);

for (; c.firstChild; )

e.insertBefore(c.firstChild, a);

b.data = "$"

}

b._reactRetry && b._reactRetry()

}

}

;

$RC("B:0", "S:0")This code inserts the new pieces of the DOM created after the Promise resolves in the right place, where the placeholder was left, and removes the placeholder and fallback.

After this DOM manipulation code is run, the DOM looks like this:

<main>

<h1>understandingreact.com</h1>

<!--$-->

<p>This message was loaded after a 5 second delay!</p>

<!--/$-->

</main>This is called out-of-order streaming and simply means taking what is streamed in and inserting it in the right, expected place in the Virtual DOM/DOM tree, even if its expected spot is before other components that finish first.

In this way if one particular component takes longer than others to execute, you don't have to wait for it to update the UI with the results of other components.

So far, however, we've only been concerning ourselves with Server Components. What about the components devs have been writing for years? What about Client Components, functions that execute in the browser?

The answer introduces an unsung hero in the RSC story: bundlers.

Bundlers and Interleaving

One of React's core tenets has always been component composition. You can split the work of deciding what the DOM should look like across many functions, and compose (that is, combine) that work together by having components be children of each other.

For RSCs to not be a dramatic shift of this core tenet, you need to be able to interleave (or weave) Server and Client Components. Client Components need to be able to be children of Server Components. That includes being able to pass props (function arguments).

What that really means is that in your component hierarchy some of your functions will run on the server and some on the client. In the end though, they all will be doing work that calculates how the part of the DOM that they generate should be structured and what it should contain.

It is the responsibility of the meta-frameworks and bundlers to make this happen, and they do. But remember abstractions have a cost. Often that cost is special rules you have to learn to use the abstraction. In this case, abstracting away some of the separation of server and client means following rules to prevent breaking the limitations of the abstraction.

In the case of RSCs there are 3 interleaving scenarios to consider. The rules are, really, about what can be imported by the component depending on where it will execute. They are rules based on how RSCs work along with the bundlers who analyze the directives and imports and pull it all together.

Client Components Imported Into Server Components

This is allowed. It makes sense that this is fine. Bundlers look at import statements to decide which code to include in their bundles, and which code will be downloaded by the client.

RSCs also participate in building the Virtual DOM. They can reference Client Components in their trees, because that Client Component code will be made available to the browser in the bundle.

Let's try adding a stateful Counter to our React course enrollment page:

// components/Counter.js

'use client';

import { useState } from 'react';

export default function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<section>

<p>{count}</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>

Enroll

</button>

</section>

);

}

// page.js

import Counter from "./components/Counter";

import DelayedMessage from "./components/DelayedMessage";

import { Suspense } from "react";

export default function Home() {

return (

<main>

<h1>understandingreact.com</h1>

<Counter />

<Suspense fallback={<p>Loading...</p>}>

<DelayedMessage />

</Suspense>

</main>

);

}Notice the use client directive at the top of the file. This is not a React feature. It's an agreed upon convention for devs to mark that a portion of the component tree is meant to be executed on the client.

That component and any components it imports will be bundled as Client Components.

The bundler will note the use client directive and include that component's code (and any it imports) in what is downloaded by the browser.

The Home and DelayedMessage RSCs will execute on the server, and their code won't be included in the bundle. The Payload from the server will look like this:

{

"type": "main",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": [

{

"type": "h1",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": "understandingreact.com"

}

},

{

"type": {

"$$type": "reference",

"id": "d",

"identifier": "L",

"type": "Lazy node"

},

"key": null,

"props": {}

},

{

"type": {

"$$type": "reference",

"id": "e",

"identifier": "",

"type": "Reference"

},

"key": null,

"props": {

"fallback": {

"type": "p",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": "Loading..."

}

},

"children": {

"$$type": "reference",

"id": "f",

"identifier": "L",

"type": "Lazy node"

}

}

}

]

}

}Notice there's a new "Lazy node" reference where the Client Component will be. That part of the Virtual DOM will be known when that Client Component executes. That will happen either when the Client Component is SSR'd (if the framework does that) or when it executes in the browser.

One more note: if you pass props from a Server Component to a Client Component, those props need to be serializable by React.

As we've seen, the props will be part of the Payload sent over the network. That means anything passed needs to be representable as a string, so it can be converted back into an object in memory on the client.

Server Components Imported Into Client Components

This isn't allowed. You can't import a component that is intended to run on the server into your component that will run in the browser.

Why? Because bundlers shouldn't send RSC functions to the client, only the Payload. Therefore there is no code to import. The bundler won't include the code for the client to download, so the RSC code isn't there to use.

It is possible to import a shared component that is viable to run on both the server and client. But if you import a shared component into a Client Component then its code will be bundled for download by the client. If you import a shared component into a Server Component, then it won't be bundled.

You might thinking: "what if I accidentally import a Server Component, how does the bundler know I don't mean to?"

Good question! This is a bit of a security problem. You could have code in a Server Component that is never meant to be downloaded and seen by others, but you accidentally import it into a Client Component and so it gets bundled in. If it has server-specific features (like connecting to a database) it will fail to execute in the browser, but if it made it into production you might have leaked some sensitive information like the address of your database.

Next.js tries to resolve this by allowing you to mark components as server only. This is a bit like tying string to your finger to remember something though. It's possible to forget to tie the string.

Other meta-frameworks are looking at safer alternatives for ensuring your server code doesn't get bundled and sent to the client.

However, once you accept an abstraction over the server-client boundary, you accept a degree of risk in forgetting those boundaries exist.

Server Components Passed as Children to Client Components

This is allowed. This is a special, interesting case. You can pass Server Components as children props to a Client Component, which is different from importing it.

If we gave our Counter function some children:

// components/Counter.js

'use client';

import { useState } from 'react';

export default function Counter({ children }) {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<section>

<p>{count}</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>

Enroll

</button>

{ children }

</section>

);

}

// page.js

import Counter from "./components/Counter";

import DelayedMessage from "./components/DelayedMessage";

import { Suspense } from "react";

export default function Home() {

return (

<main>

<h1>understandingreact.com</h1>

<Counter>

<p>Server Text</p>

</Counter>

<Suspense fallback={<p>Loading...</p>}>

<DelayedMessage />

</Suspense>

</main>

);

}It works just fine, even though the Counter function executes on the client, and the children passed to it (<p>Server Text</p>) were processed on the server!

Why does this work? Because what you're really passing is a portion of the Virtual DOM tree (the results of executing the code), not the Server Component code to be executed.

The Payload looks like this:

{

"children": [

{

"type": "h1",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": "understandingreact.com"

}

},

{

"type": {

"$$type": "reference",

"id": "d",

"identifier": "L",

"type": "Lazy node"

},

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": {

"type": "p",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": "Server Text"

}

}

}

},

{

"type": {

"$$type": "reference",

"id": "e",

"identifier": "",

"type": "Reference"

},

"key": null,

"props": {

"fallback": {

"type": "p",

"key": null,

"props": {

"children": "Loading..."

}

},

"children": {

"$$type": "reference",

"id": "f",

"identifier": "L",

"type": "Lazy node"

}

}

}

]

}

}Notice the "Server Text" portion of the Payload. It's already passed as a prop to the Client Component. It's as if you'd simply written the JSX in the Payload directly in your Client Component.

Bundlers: The Unsung Heroes

All of this serves to show an important point. React Server Components, in many ways, are a bundler feature.

The bundler analyzes your code, and ensures that Client Components are in the bundle and helps ensure references to those Client Components appear properly in the Payload.

Bundlers are a first-class citizen in React. If you look at the React codebase you'll find folders like:

/react-server-dom-parcel

/react-server-dom-turbopack

/react-server-dom-webpack

//...and moreInside those folders are code having to do with Flight, helping the bundled code get all of this right.

Because bundlers are the unsung hero of RSCs, it also means that other conventions are possible. A meta-framework doesn't have to buy-in to the use client approach that Next.js uses. TanStack Start, for example, is implementing RSCs simply as functions that "return JSX" (i.e. the Flight format).

React has provided an API: streaming Flight data. It's up the meta-frameworks to iterate and innovate on how they use that API.

Hooks and RSCs

Execution on the server comes with some advantages, but also some limitations.

React doesn't just store the structure of elements in the Virtual DOM, it stores state. When you write:

const [counter, setCounter] = useState(0);in a component, it places that data in a node on a linked list attached to your component's place in the Virtual DOM. In reality, then, that state is sitting in a JavaScript object in the client browser's memory.

So, React Server Components, by their very nature, can't use those hooks. They run in the wrong environment to do that.

That means, ultimately, that RSCs are non-interactive. Interactivity in React generally means triggering a client-side React re-render, and that happens by updating state.

This means that as your app gains more and more interactive functionality, you tend to refactor your Server Components into Client and Server Component compositions.

Whenever you need something like useReducer or useState, you need a Client Component.

If you keep in mind where your components are executing, you'll use (or not use) Hooks properly.

To Hydrate or Not to Hydrate

I wanted to mention for a moment a point of common confusion. Do RSCs hydrate?

The answer is no. Hydration is about re-executing the actual functions on the client, in order to build the Virtual DOM so that events can be hooked to their handlers.

In React, when we click a button, that event is sent way up the DOM tree to React's root, where React then determines which component should handle the click (the answer is the component that was responsible for creating the button).

Thus you need the Virtual DOM in place and the code that handles the click so that React can respond properly to the event.

RSCs are non-interactive. They won't set state, they won't handle clicks, at least not via React's normal approach. Their code isn't sent to the client for execution, so by definition they don't hydrate.

However, they are part of building the Virtual DOM. They are part of tree reconciliation. The fact that they don't hydrate doesn't mean they aren't in the tree during hydration. They are.

Refetching and Reconciliation

In real world apps you likely are not not just concerned with the initial load of a page, but concerned with refetching those server components.

That means asking the server to re-execute those components (perhaps with new props), and provide new Payload data to update the Virtual DOM with.

For example, if we are paginating through a list of data, and that list is generated by an RSC, we want to get a different set of data if the route is /page/1 versus /page/2.

This is an advantage of RSCs, and most likely integrated with the meta-frameworks' router. The meta-framework doesn't have to do a full page refresh, even though the UI is calculated on the server.

By its very nature, RSCs can stream Virtual DOM definitions to the client, and React can then perform client-side reconciliation as normal. In other words, the page doesn't have to refresh and you don't lose other state on the page.

In this aspect RSCs can provide the best of both rendering worlds. They can run on the server, but update as if they were executed on the client.

Now that we've covered how RSCs really work, this hopefully makes more intuitive sense. React already updates the DOM by diffing the Virtual DOM. So if we can get Virtual DOM data from the server, it can do what it always has.

The Bundle Size Confusion

For over a decade now, I've pushed having deep understanding how the tools you use work. That's what my courses have always been about.

I'm happy that so many students have appreciated that approach. Yet, every now and again, someone complains "too much theory, just learn by doing".

One of the major values, however, of understanding how the tools, libraries, and frameworks we use work is we can make good, informed architectural decisions.

For example, there's been confusion in the Next.js world on the benefits of RSCs. There's a pretty extraordinary discussion on the next.js code repository about the __next_f() function.

Devs who started to use RSCs discovered that there was duplicated data being passed to this function in script tags at the bottom of their pages. Some asked why it was there and if it could be turned off.

What is this doubled data? You guessed it. The Payload! Those function calls that were streamed in ultimately pass that Payload data to React to create the Virtual DOM. This is shocking if you don't understand how all this works.

The issue is that it increases bandwidth usage, which many were complaining about. You're sending more data across the network.

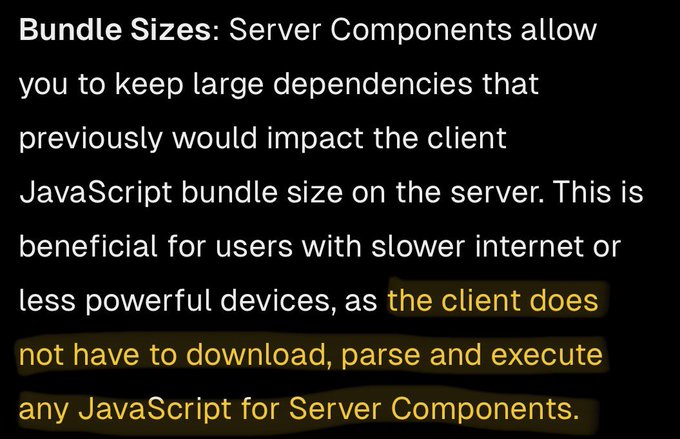

Why were people surprised? Well, Vercel originally described RSCs this way on Next.js' documentation site:

The phrase "the client down not have download, parse, and execute any JavaScript for Server Components" was the misleading one. It isn't really true. Vercel was referring to the actual JavaScript code of the Server Components, but they used the word any.

I had an interesting branching conversation with them on social media. I like to think that was part of the reason the wording was later changed (kudos to Vercel for changing it):

The new description says that Server Components "can reduce the amount of client-side JavaScript needed". This is true! But they can also increase it, because the Payload, in a sense, is JavaScript, or at least data passed to JavaScript functions.

The core misunderstanding of devs is that bundle size and bandwidth usage are not the same thing.

Server Component code is not in the bundle! So they do reduce bundle size! But the Payload is doubled data, and if that data is large (like a big blog post like this one) you'll end up sending more bytes than you save.

When Should You Use RSCs?

So, when should you use RSCs? The right answer, as always, is "it depends". Being armed with an accurate mental model of how they work will help you make that architectural choice.

For my part, I wouldn't use RSCs for a big blog post like this one. The bandwidth usage doesn't make sense to me. I'd use something like Astro for content-heavy sites and apps.

On the other hand, if I had a lot of DB access and complex logic, I might offload that to the server by doing it on a Server Component. The same if I needed to use large JavaScript libraries to produce a relatively small amount of content. If the bundle to Payload trade off is worth it, RSCs make sense to me.

If I have a highly interactive app, and I'm iterating and constantly adding features, I'd also be hesistant to do too much client/server refactoring and might keep it as mostly Client Components.

There are simply too many variables to make a hard recommendation. The best I can do is what I tried to do here in this post: help you understand, so you can come to an informed decision.

Looking Forward

What's the future of React Server Components? It isn't entirely clear. React has made the API, and meta-frameworks are using it.

I think the TanStack Start approach of functions that return Virtual DOM, rather than full Server Components, will be popular. But for some uses, Next.js' approach will work well.

I hope to see incremental improvements in security and performance. For example, if a branch of the Virtual DOM is all Server Components, some reconciliation or hydration optimizations could be made to skip that part of the tree.

Diving Deeper

I hope you found this post useful to your understanding of React Server Components. For a deep dive like this into all of React, from scratch, you can enroll in my full course Understanding React.

Over 27 modules and 16.5 hours of video content we dive into React's source code together, to build the most valuable tool in a developer's toolbelt: an accurate mental model.

Happy coding!