Understanding React Compiler

React's core architecture calls the functions you give it (i.e. your components) over and over. This fact both contributed to its popularity by simplifying its mental model, and created a point of possible performance issues. In general, if your functions do expensive things, then your app will be slow.

Performance tuning, therefore, became a pain point for devs, as they had to manually tell React which functions should be re-run and when. The React team has now provided a tool called the React Compiler to automate that manual work performance tuning for devs, by rewriting their code.

What does React Compiler do to your code? How does it work under-the-hood? Should you use it? Let's dive in.

To gain a complete, accurate mental model of React by deep diving into its internals, check out my new course Understanding React where we dig into React's source code. I've found a deep understanding of React's internals greatly helps even devs with years of React experience.

Compilers, Transpilers, and Optimizers

We hear the terms compiler, transpiler, and optimizer thrown about the modern JavaScript ecosystem. What are they?

Transpilation

A transpiler is a program that analyzes your code and outputs functionally equivalent code in a different programming language, or an adjusted version of your code in the same programming language.

React devs have been using a transpiler for years to convert JSX to the code that is actually run by the JavaScript engine. JSX is essentially shorthand for building trees of nested function calls (which then build trees of nested objects).

Writing nested function calls is cumbersome and error-prone, so JSX makes the developer's life easier, and a transpiler is needed to analyze the JSX and convert it into those function calls.

For example, if you wrote the following React code using JSX:

Note that, for ease of reading, all code in this blog post is intentionally oversimplified.

function App() {

return <Item item={item} />;

}

function Item({ item }) {

return (

<ul>

<li>{ item.desc }</li>

</ul>

)

}it becomes, after transpilation:

function App() {

return _jsx(Item, {

item: item

});

}

function Item({ item }) {

return _jsx("ul", {

children: _jsx("li", {

children: item.desc

})

});

}This is the code that is actually sent to the browser. Not HTML-like syntax, but nested function calls passing plain JavaScript objects that React calls 'props'.

The result of transpilation shows why you can't use if-statements easily inside JSX. You can't use if-statements inside function calls.

You can quickly generate and examine the output of transpiled JSX using Babel.

Compilation and Optimization

So what's the difference between a transpiler and a compiler? It depends on who you ask, and what their education and experience is. If you come from a computer science background you might have mostly been exposed to compilers as a program that converts the code you write into machine language (the binary code that a processor actually understands).

However, "transpilers" are also called "source-to-source compilers". Optimizers are also called "optimizing compilers". Transpilers and optimizers are types of compilers!

Naming things is hard, so there will be disagreement about what constitutes a transpiler, compiler, or optimizer. The important thing to understand is that transpilers, compilers, and optimizers are programs that take a text file containing your code, analyze it, and produce a new text file of different but functionally equivalent code. They may make your code better, or add abilities that it didn't have before by wrapping bits of your code in calls to other people's code.

Compilers, transpilers, and optimizers are programs that take a text file containing your code, analyze it, and produce different but functionally equivalent code.

That last part is what React Compiler does. It creates code functionally equivalent to what you wrote, but wraps bits of it in calls to code the React folks wrote. In that way, your code is rewritten into something that does what you intended, plus more. We'll see exactly what the "more" is in a bit.

Abstract Syntax Trees

When we say your code is "analyzed", we mean the text of your code is parsed character-by-character and algorithms are run against it to figure out how to adjust it, rewrite it, add features to it, etc. The parsing usually results in an abstract syntax tree (or AST).

While that sounds fancy, it really is just a tree of data that represents your code. It is then easier to analyze the tree, rather than the code you wrote.

For example, let's suppose you have a line in your code that looks like this:

const item = { id: 0, desc: 'Hi' };the abstract syntax tree for that line of code might end up looking something like this:

{

type: VariableDeclarator,

id: {

type: Identifier,

name: Item

},

init: {

type: ObjectExpression,

properties: [

{

type: ObjectProperty,

key: id,

value: 0

},

{

type: ObjectProperty,

key: desc,

value: 'Hi'

}

]

}

}The generated data structure describes your code as you wrote it, breaking it down into small defined pieces containing both what type of thing the piece is and any values associated with it. For example desc: 'Hi' is an ObjectProperty with a key called 'desc' and a value of 'Hi'.

This is the mental model you should have when you imagine what is happening to your code in a transpiler/compiler/etc. People wrote a program that takes your code (the text itself), converts it into a data structure, and performs analysis and work on it.

The code that is generated ultimately comes from this AST as well as perhaps some other intermediate languages. You can imagine looping over this data structure and outputting text (new code in the same language or a different one, or adjusting it in some way).

In the case of React Compiler it utilizes both an AST and an intermediate language to generate new React code from the code you write. It's important to remember that React Compiler, like React itself, is just other people's code.

When it comes to compilers, transpilers, optimizers, and the like, don't think of these tools as mysterious black boxes. Think of them as things that you could build, if you had the time.

React's Core Architecture

Before we move on to React Compiler itself, there's a few more concepts we need to have clear.

Remember that we said React's core architecture is both a source of its popularity, but also a potential performance issues? We saw that when you write JSX, you're actually writing nested function calls. But you are giving your functions to React, and it will decide when to call them.

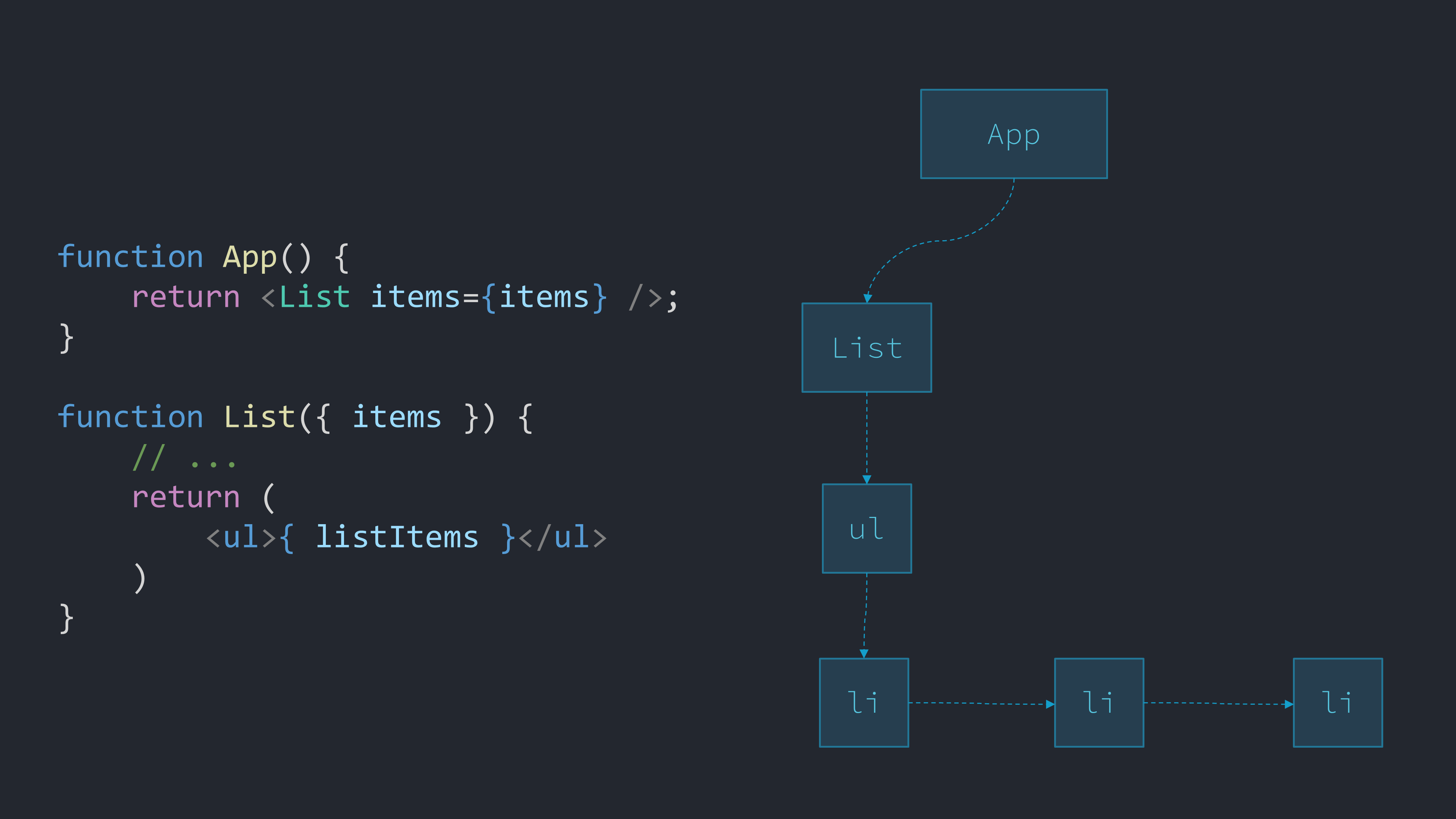

Let's take the beginnings of a React app for dealing with a large list of items. Let's suppose our App function gets some items, and our List function processes and shows them.

function App() {

// TODO: fetch some items here

return <List items={items} />;

}

function List({ items }) {

const pItems = processItems(items);

const listItems = pItems.map((item) => <li>{ item }</li>);

return (

<ul>{ listItems }</ul>

)

}Our functions return plain JavaScript objects, like a ul object which contains its children (which here will end up being multiple li objects). Some of these objects like ul and li are built-in to React. Others are the ones we create, like List.

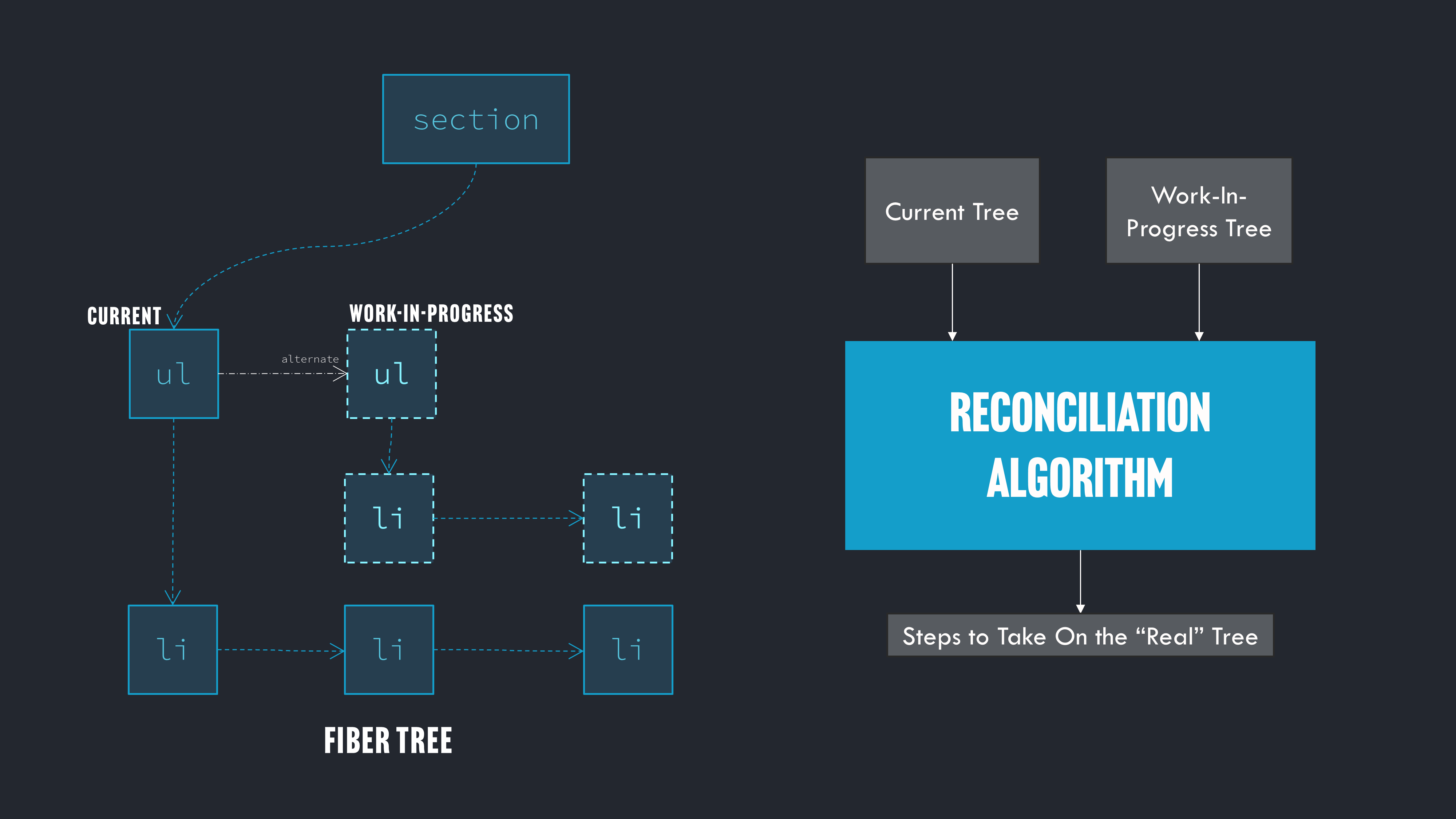

Ultimately, React will build a tree from all these objects called the Fiber tree. Each node in the tree is called a Fiber or Fiber node. The idea of creating our own JavaScript object tree of nodes to describe a UI is called creating a "Virtual DOM".

React actually keeps two branches that can fork out from each node of the tree. One branch is called is of the "current" state of that branch of the tree (which matches the DOM), and the other the "work-in-progress" state of that branch of the tree which matches the tree created from what our functions returned when they were re-run.

React will then compare those two trees to decide what changes need to made to the actual DOM, so that the DOM matches the work-in-progress side of the tree. This process is called "reconciliation".

Master React From The Inside Out

If you are enjoying this deep dive, you'll love and benefit from understanding all of React at this level. My course Understanding React takes you through 17 hours of React's source code, covering JSX, Fiber, hooks, forms, reconciliation, and more, updated for React 19.

Learn More →Thus, depending on what other functionality we add to our app, React may choose to call our List function over and over, whenever it thinks the UI might need to be updated. This makes our mental model fairly straightforward. Whenever the UI might need to be updated (for example, in response to a user action like clicking a button), the functions that define the UI will be called again, and React will figure out how to update the actual DOM in the browser to match how our functions say the UI should look.

But if the processItems function is slow, then every call to List will be slow, and our whole app will be slow as we interact with it!

Memoization

A solution in programming to deal with repeated calls to expensive functions is to cache the results of the function. This process is called memoization.

For memoization to work, the function must be "pure". That means that if you pass the same inputs to the function, you always get the same output. If that's true, then you can take the output and store it in a way that it's related to the set of inputs.

The next time you call the expensive function, we can write code to look at the inputs, check the cache to see if we've already run the function with those inputs, and if we have, then grab the stored output from cache rather than calling the function again. No need to call the function again since we know the output will be the same as the last time those inputs were used.

If the processItems function from the previous used implemented memoization it might look something like:

function processItems(items) {

const memOutput = getItemsOutput(items);

if (memOutput) {

return memOutput;

} else {

// ...run expensive processing

saveItemsOutput(items, output);

return output;

}

}We can imagine that the saveItemsOutput function stores an object that saves both items and the associated output from the function. The getItemsOutput will look to see if items is already stored, and if it is we return the related cached output without doing any more work.

For React's architecture of calling functions over and over, memoization becomes a vital technique for helping to keep apps from becoming slow.

Hook Storage

There's one more piece of React's architecture to understand in order to understand React Compiler.

React will look at calling your functions again if the "state" of the app changes, meaning the data that the creation of the UI is dependent on. For example a piece of data might be "showButton" which is true or false, and the UI should show or hide the button based on the value of that data.

React stores state on the client's device. How? Let's take the React app that will render and interact with a list of items. Suppose we will eventually store a selected item, process the items client side for rendering, handle events, and sort the list. Our app might start to look something like below.

function App() {

// TODO: fetch some items here

return <List items={items} />;

}

function List({ items }) {

const [selItem, setSelItem] = useState(null);

const [itemEvent, dispatcher] = useReducer(reducer, {});

const [sort, setSort] = useState(0);

const pItems = processItems(items);

const listItems = pItems.map((item) => <li>{ item }</li>);

return (

<ul>{ listItems }</ul>

)

}What is really happening here when the useState and useReducer lines are executed by the JavaScript engine? The node of the Fiber tree created from our List component has some more JavaScript objects attached to it to store our data. Each of those objects is connected to each other in a data structure called a linked list.

By the way, a lot of devs think useState is the core unit of state management in React. But it isn't! It's actually a wrapper for a simple call to useReducer.

So, when you call useState and useReducer, React will attach the state to the Fiber tree that sits around while our app runs. Thus state remains available as our functions keep re-running.

How hooks are stored also explains the "rule of hooks" that you can't call a hook inside a loop or an if-statement. Every time you call a hook, React moves to the next item in the linked list. Thus, the number of times you call hooks must be consistent, or React would sometimes be pointing at the wrong item in the linked list.

Ultimately, hooks are just objects designed to hold data (and functions) in the user's device memory. This is key to understanding what React Compiler really does. But there's more.

Memoization in React

React combines the idea of memoization and its idea of hook storage. You can memoize the results of entire functions you give React that are part of the Fiber Tree (like List), or individual functions you call within them (like processItems).

Where is the cache stored? On the Fiber tree, just like state! For example the useMemo hook stores the inputs and outputs on the node that calls useMemo.

So, React already has the idea of storing the results of expensive functions in linked lists of JavaScript objects that are part of the Fiber Tree. That's great, except for one thing: maintenance.

Memoization in React can be cumbersome, because you have to explicitly tell React what inputs the memoization depends on. Our call to processItems becomes:

const pItems = useMemo(processItems(items), [items]);The array at the end being the list of 'dependencies', that is the inputs that, if changed, tell React the function should be called again. You have to make sure you get those inputs right, or memoization won't work properly. It becomes a clerical chore to keep up with.

React Compiler

Enter React Compiler. A program that analyzes the text of your React code, and produces new code ready for JSX transpilation. But that new code has some extra things added to it.

Let's look at what React Compiler does to our app in this case. Before compilation it was:

function App() {

// TODO: fetch some items here

return <List items={items} />;

}

function List({ items }) {

const [selItem, setSelItem] = useState(null);

const [itemEvent, dispatcher] = useReducer(reducer, {});

const [sort, setSort] = useState(0);

const pItems = processItems(items);

const listItems = pItems.map((item) => <li>{ item }</li>);

return (

<ul>{ listItems }</ul>

)

}after compilation it becomes:

function App() {

const $ = _c(1);

let t0;

if ($[0] === Symbol.for("react.memo_cache_sentinel")) {

t0 = <List items={items} />;

$[0] = t0;

} else {

t0 = $[0];

}

return t0;

}

function List(t0) {

const $ = _c(6);

const { items } = t0;

useState(null);

let t1;

if ($[0] === Symbol.for("react.memo_cache_sentinel")) {

t1 = {};

$[0] = t1;

} else {

t1 = $[0];

}

useReducer(reducer, t1);

useState(0);

let t2;

if ($[1] !== items) {

const pItems = processItems(items);

let t3;

if ($[3] === Symbol.for("react.memo_cache_sentinel")) {

t3 = (item) => <li>{item}</li>;

$[3] = t3;

} else {

t3 = $[3];

}

t2 = pItems.map(t3);

$[1] = items;

$[2] = t2;

} else {

t2 = $[2];

}

const listItems = t2;

let t3;

if ($[4] !== listItems) {

t3 = <ul>{listItems}</ul>;

$[4] = listItems;

$[5] = t3;

} else {

t3 = $[5];

}

return t3;

}That's a lot! Let's break down a bit of the now rewritten List function to understand it.

It starts off with:

const $ = _c(6);That _c function (think "c" for "cache") creates an array that's stored using a hook. React Compiler analyzed our Link function and decided, to maximize performance, we need to store six things. When our function is first called, it stores the results of each of those six things in that array.

It's the subsequent calls to our function where we see the cache in action. For example, just looking at the area where we call processItems:

if ($[1] !== items) {

const pItems = processItems(items);

let t3;

if ($[3] === Symbol.for("react.memo_cache_sentinel")) {

t3 = (item) => <li>{item}</li>;

$[3] = t3;

} else {

t3 = $[3];

}

t2 = pItems.map(t3);

$[1] = items;

$[2] = t2;

} else {

t2 = $[2];

}The entire work around processItems, both calling the function and generating the lis, is wrapped in a check to see if the cache in the second position of the array ($[1]) is the same input as the last time the function was called (the value of items which is passed to List).

If they are equal, then the third position in the cache array ($[2]) is used. That stores the generated list of all the lis when items is mapped over. React Compiler's code says "if you give me the same list of items as the last time you called this function, I will give you the list of lis that I stored in cache the last time".

If the items passed is different, then it calls processItems. Even then, it uses the cache to store what one list item looks like.

if ($[3] === Symbol.for("react.memo_cache_sentinel")) {

t3 = (item) => <li>{item}</li>;

$[3] = t3;

} else {

t3 = $[3];

}See the t3 = line? Rather than recreating the arrow function that returns the li, it stores the function itself in the fourth position in the cache array ($[3]). This saves the JavaScript engine the work of creating that small function the next time List is called. Since that function never changes, the initial if-statement is basically saying "if this spot in the cache array is empty, cache it, otherwise get it from cache".

In this way, React caches values and memoizes the results of function calls automatically. The code it outputs is functionally equivalent to the code we wrote, but includes code to cache these values, saving performance hits when our functions are called over and over by React.

React Compiler is caching, though, at a more granular level than what a dev typically does with memoization, and is doing so automatically. This means devs don't have to manually manage dependencies, or memoization. They can just write code, and from it React Compiler will generate new code that utilizes caching to make it faster.

It's worth noting that React Compiler is still producing JSX. The code that is actually run is the result of React Compiler after JSX transpilation.

The List function actually run in the JavaScript engine (sent to the browser or on the server) looks like this:

function List(t0) {

const $ = _c(6);

const {

items

} = t0;

useState(null);

let t1;

if ($[0] === Symbol.for("react.memo_cache_sentinel")) {

t1 = {};

$[0] = t1;

} else {

t1 = $[0];

}

useReducer(reducer, t1);

useState(0);

let t2;

if ($[1] !== items) {

const pItems = processItems(items);

let t3;

if ($[3] === Symbol.for("react.memo_cache_sentinel")) {

t3 = item => _jsx("li", {

children: item

});

$[3] = t3;

} else {

t3 = $[3];

}

t2 = pItems.map(t3);

$[1] = items;

$[2] = t2;

} else {

t2 = $[2];

}

const listItems = t2;

let t3;

if ($[4] !== listItems) {

t3 = _jsx("ul", {

children: listItems

});

$[4] = listItems;

$[5] = t3;

} else {

t3 = $[5];

}

return t3;

}React Compiler added an array for caching values, and all the needed if-statements to do so. The JSX transpiler converted the JSX into nested function calls. There is a not-insignificant difference between what you wrote and what the JavaScript engine runs. We are trusting other people's code to produce something that matches our original intent.

Trading Processor Cycles for Device Memory

Memoization and caching in general means trading processing for memory. You save on the processor having to execute expensive operations, but you avoid that by using up space to store things in memory.

If you use React Compiler, that means you are saying "store as much as you can" in the device's memory. If the code is running on the user's device in the browser, that's an architectural consideration to keep in mind.

Likely, this won't be a real problem for many React apps. But if you are dealing with large amounts of data in your apps, then device memory usage is something you should at least be aware of and keep an eye on if you use React Compiler once it leaves the experimental stage.

Abstractions and Debugging

Compilation in all its forms amounts to a layer of abstraction between the code you write and the code that is actually being run.

As we saw, in the case of React Compiler, to understand what is actually sent to the browser you need to take your code and run it through React Compiler, and then take that code and run it through a JSX transpiler.

There is a downside to adding layers of abstraction to our code. They can make our code harder to debug. That doesn't mean we shouldn't use them. But you should keep clearly in mind that the code you need to debug isn't just yours, but the code the tool is generating.

What makes a real difference in your ability to debug code generated from an abstraction layer, is to have an accurate mental model of the abstraction. Fully understanding how React Compiler works will give you the ability to debug the code it writes, improving your dev experience and lowering the stress your dev life.

Dive Deeper

If you found this blog post helpful, you might be interested in doing a similar deep dive across all of React's features in my 16.5 hour course Understanding React. You get lifetime access, all source code, and a certificate of completion.

I read every line of React's source code, and then every line of React Compiler's source code. Why? So I could explain React from the internals level, under-the-hood.

React itself is a massive abstraction layer on top of web fundamentals. As is the case with so many abstractions, I find that most devs using React have an inaccurate mental model of how it works, which greatly impacts how they build and debug React-based applications. But you can understand React deeply.

New content on React 19 has been added to the course. Check the course out. You can also watch the first 6 hours of the course for free on my YouTube channel, which I'll put here.

I hope you'll join me on a journey of, not just imitating someone else writing code, but truly understanding what you're doing.

-- Tony